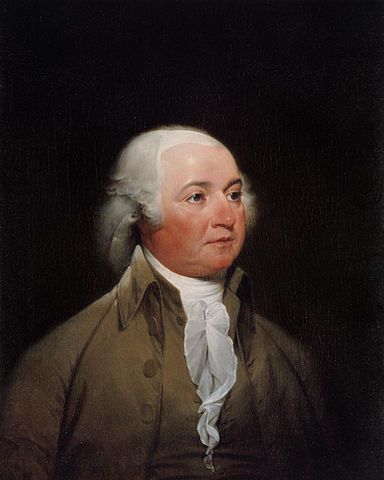

John Adams, whose worth and services Daniel Webster, six years after uttering those words, pointed out in Fanueil Hall when the old statesman died, was probably the most influential member of the Continental Congress, after Washington, since he was its greatest orator and its most impassioned character. He led the Assembly, as Henry Clay afterwards led the Senate, and Canning led the House of Commons, by that inspired logic which few could resist. Jefferson spoke of him as "the colossus of debate." It is the fashion in these prosaic times to undervalue congressional and parliamentary eloquence, as a vain oratorical display; but it is this which has given power to the greatest leaders of mankind in all free governments,--as illustrated by the career of such men as Demosthenes, Pericles, Cicero, Chatham, Fox, Mirabeau, Webster, and Clay; and it is rarely called out except in great national crises, amid the storms of passion and agitating ideas. Jefferson affected to sneer at it, as exhibited by Patrick Henry; but take away eloquence from his own writings and they would be commonplace. All productions of the human intellect are soon forgotten unless infused with sentiments which reach the heart, or excite attention by vividness of description, or the brilliancy which comes from art or imagination or passion. Who reads a prosaic novel, or a history of dry details, if ever so accurate? How few can listen with interest to a speech of statistical information, if ever so useful,--unless illuminated by the oratorical genius of a Gladstone! True eloquence is a gift, as rare as poetry; an inspiration allied with genius; an electrical power without which few people can be roused, either to reflection or action. This electrical power both the Adamses had, as remarkably as Whitefield or Beecher. No one can tell exactly what it is, whether it is physical, or spiritual, or intellectual; but certain it is that a speaker will not be listened to without it, either in a legislative hall, or in the pulpit, or on the platform. And hence eloquence, wherever displayed, is really a great power, and will remain so to the end of time.

At the first session of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, in 1774, although it was composed of the foremost men in the country, very little was done, except to recommend to the different provinces the non-importation of British goods, with a view of forcing England into conciliatory measures; at which British statesmen laughed. The only result of this self-denying ordinance was to compel people to wear homespun and forego tea and coffee and other luxuries, while little was gained, except to excite the apprehension of English merchants. Yet this was no small affair in America, for we infer from the letters of John Adams to his wife that the habits of the wealthy citizens of Philadelphia were even then luxurious, much more so than in Boston. We read of a dinner given to Adams and other delegates by a young Quaker lawyer, at which were served ducks, hams, chickens, beef, pig, tarts, cream, custards, jellies, trifles, floating islands, beer, porter, punch, wine, and a long list of other things. All such indulgences, and many others, the earnest men and women of that day undertook cheerfully to deny themselves.

Adams returned these civilities by dining a party on salt fish,--perhaps as a rebuke to the costly entertainments with which he was surfeited, and which seemed to him unseasonable in "times that tried men's souls." But when have Philadelphia Quakers disdained what is called good living?

Adams, at first delighted with the superior men he met, before long was impatient with the deliberations of the Congress, and severely criticised the delegates. "Every man," wrote he, "upon every occasion must show his oratory, his criticism, and his political abilities. The consequence of this is that business is drawn and spun out to an immeasurable length. I believe, if it was moved and seconded that we should come to a resolution that three and two make five, we should be entertained with logic and rhetoric, law, history, politics, and mathematics; and then--we should pass the resolution unanimously in the affirmative. These great wits, these subtle critics, these refined geniuses, these learned lawyers, these wise statesmen, are so fond of showing their parts and powers as to make their consultations very tedious. Young Ned Rutledge is a perfect bob-o-lincoln,--a swallow, a sparrow, a peacock; excessively vain, excessively weak, and excessively variable and unsteady, jejune, inane, and puerile." Sharp words these! This session of Congress resulted in little else than the interchange of opinions between Northern and Southern statesmen. It was a mere advisory body, useful, however, in preparing the way for a union of the Colonies in the coming contest. It evidently did not "mean business," and "business" was what Adams wanted, rather than a vain display of abilities without any practical purpose.

The second session of the Congress was not much more satisfactory. It did, however, issue a Declaration of Rights, a protest against a standing army in the Colonies, a recommendation of commercial non-intercourse with Great Britain, and, as a conciliatory measure, a petition to the king, together with elaborate addresses to the people of Canada, of Great Britain, and of the Colonies. All this talk was of value as putting on record the reasonableness of the American position: but practically it accomplished nothing, for, even during the session, the political and military commotion in Massachusetts increased; the patriotic stir of defence was evident all over the country; and in April, 1775, before the second Continental Congress assembled (May 10) Concord and Lexington had fired the mine, and America rushed to arms. The other members were not as eager for war as Adams was. John Dickinson of Pennsylvania--wealthy, educated moderate, conservative--was for sending another petition to England, which utterly disgusted Adams, who now had faith only in ball-cartridges, and all friendly intercourse ended between the countries. But Dickinson's views prevailed by a small majority, which chafed and hampered Adams, whose earnest preference was for the most vigorous measures. He would seize all the officers of the Crown; he would declare the Colonies free and independent at once; he would frankly tell Great Britain that they were determined to seek alliances with France and Spain if the war should be continued; he would organize an army and appoint its generals. The Massachusetts militia were already besieging the British in Boston; the war had actually begun. Hence he moved in Congress the appointment of Colonel George Washington, of Virginia, as commander-in-chief,--much to the mortification of John Hancock, president of the Congress, whose vanity led him to believe that he himself was the most fitting man for that important post.

In moving for this appointment, Adams ran some risk that it would not be agreeable to New England people, who knew very little of Washington aside from his having been a military man, and one generally esteemed; but Adams was willing to run the risk in order to precipitate the contest which he knew to be inevitable. He knew further that if Congress would but, as he phrased it, "adopt the army before Boston" and appoint Colonel Washington commander of it, the appointment would cement the union of the Colonies,--his supreme desire. New England and Virginia were thus leagued in one, and that by the action of all the Colonies in Congress assembled.

Although Mr. Adams had been elected chief-justice of Massachusetts, as its ablest lawyer, he could not be spared from the labors of Congress. He was placed on the most important committees, among others on one to prepare a resolution in favor of instructing the Colonies to favor State governments, and, later on, the one to draft the Declaration of Independence, with Jefferson, Franklin, Sherman, and Livingston. The special task was assigned to Jefferson, not only because he was able with his pen, but because Adams was too outspoken, too imprudent, and too violent to be trusted in framing such a document. Nothing could curb his tongue. He severely criticised most every member of Congress, if not openly, at least in his confidential letters; while in his public efforts with tongue and pen he showed more power than discretion.

At that time Thomas Paine appeared in America as a political writer, and his florid pamphlet on "Common Sense" was much applauded by the people. Adams's opinion of this irreligious republican is not favorable: "That part of 'Common Sense' which relates to independence is clearly written, but I am bold enough to say there is not a fact nor a reason stated in it which has not been frequently urged in Congress," while "his arguments from the Old Testament to prove the unlawfulness of monarchy are ridiculous."

The most noteworthy thing connected with Adams's career of four years in Congress was his industry. During that time he served on at least one hundred committees, and was always at the front in debating measures of consequence. Perhaps his most memorable service was the share he had in drawing the Articles of Confederation, although he left Philadelphia before his signature could be attached. This instrument had great effect in Europe, since the States proclaimed union as well as independence. It was thenceforward easier for the States to borrow money, although the Confederation was loose-jointed and essentially temporary; nationality was not established until the Constitution was adopted. Adams not only guided the earliest attempts at union at home, but was charged with great labors in connection with foreign relations, while as head of the War Board he had enough both of work and of worry to have broken down a stronger man. Always and everywhere he was doing valuable work.

On the mismanagement of Silas Deane, as an American envoy in Paris, it became necessary to send an abler man in his place, and John Adams was selected, though he was not distinguished for diplomatic tact. Nor could his mission be called in all respects a success. He was too imprudent in speech, and was not, like Franklin, conciliatory with the French minister of Foreign Affairs, who took a cordial dislike to him, and even snubbed him. But then it was Adams who penetrated the secret motives of the Count de Vergennes in rendering aid to America, which Franklin would not believe, or could not see. Nor were the relations of Adams very pleasant with the veteran Franklin himself, whose merits he conceived to be exaggerated, and of whom it is generally believed he was envious. He was as fussy in business details as Franklin was easy and careless. He thought that Franklin lived too luxuriously and was too fond of the praises of women.